Making VoIP Calls with Antique Rotary Phones

One of the worst parts of modern life is how unsatisfying it is to hang up on somebody. Tapping on the ‘End Call’ button on an iPhone or angrily clicking ‘Leave Meeting’ on Zoom just isn’t nearly as fun as slamming down the handset on a real phone.

This particular project was to breathe some life into the antique Northern Telecom phone from my grandparents’ house by attaching it to a modern VoIP system. This was surprisingly difficult, but very satisfying as the result is essentially a free ‘vintage’ landline for my home.

The Phone

The device in question is a NT analog phone, based on the classic Western Electric model 500. The models are very similar with only minor differences, for example the printing of the numbers on the dial is slightly different for models from Canada. Based on the stamp marks on the bottom, I believe this phone was manufactured in 1969 and installed shortly after, which does match up with when my grandparents would have purchased their first phone.

On its own, this telephone would not work with any modern telecom system. The ‘pulse dial’ that it produces is not compatible with modern telephone equipment and VoIP adapters alike.

I can’t get a good source on this, but most telephone exchanges in urban areas haven’t accepted pulse dial signals for decades. Some areas may still accept pulse signalling depending on the age of their equipment, but in 2021 I doubt there are many left. Seeing as how Dual-Tone Multi-Frequency (DTMF) signalling has been the standard for over forty years, nearly all VoIP equipment was manufactured without support for old devices.

Pulse Dialling

Pulse dialing is very simple as it is derived from the mechanical rotation of the dial. As it turns from the dialed digit back to the resting position it toggles the local loop voltage to transmit the data to the FXO. In the old days, these voltage ’ticks’ were used to rotate mechanical switches in the exchange stations to connect physical circuits needed to complete a call.

DTMF Dialling

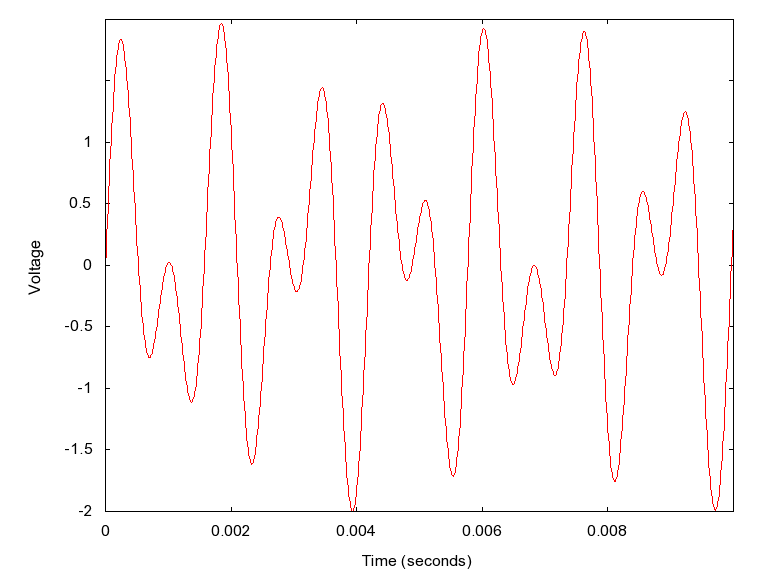

DTMF on the other hand is an in-band signalling method using eight different frequencies transmitted in pairs. To use the example from Wikipedia, to transmit a ‘1’ on a DTMF system it will transmit two tones, 1209Hz and 695Hz together:

These tones are the beeps we’re used to hearing when dialing. Even my cell phone creates these tones when you type on the on-screen keypad in the ‘Phone’ app, though it’s mostly for ‘cosmetic’ reasons. Theoretically one could use these tones to dial on a rotary phone if you held the speaker of the cell phone up to the microphone of the telephone while dialling, though I couldn’t get it to reliably work.

Converting signalling

So, the first piece of equipment I needed was a pulse-tone converter. Indeed, such a device does exist to convert the ’ticks’ produced by the rotary dial to the ‘beeps’ produced by most keypad phones. I was a little squeamish about tearing apart a working antique, so I opted to buy an external dial tone converter box from OldPhoneWorks.

It’s a very simple device which listens for the pulse tones and using tiny DSP chips converts them to DTMF tones. If your only goal was to use the old phone with a POTS landline this would be sufficient, but I want to connect this to VoIP.

The SIP ATA box

There are heaps of Analog Telephone Adapter (ATA) boxes on the market, but in the interest of keeping this project low-cost I opted to purchase a new-old-stock Linksys PAP2T-NA device from eBay. I wasn’t too worried about security since the device sits in the ’enclave’ part of my home network isolated from personal devices, and won’t have any ports forwarded to it. I was initially worried that my custom Linux router would cause issues with the UDP traffic RTP creates, but it handled it wonderfully.

Setup was fairly straightforward to begin with, entering my sub-account credentials and SIP proxy server. Without too much fuss the device was registered and communicating with my provider.

However, I did run into some strange issues after initially setting it up. First, the ring pattern was intermittent and sounded strange. After a couple test calls I also found that both sides of the conversation were quiet when using the vintage phone. With some fiddling, I rectified these by increasing power limits slightly:

- Changed ring waveform to Sinusoid

- Changed ring voltage to 90

- Changed FXS port power limit -3 -> 5

- Changed FXS port input & output gain -3 -> 0

I chalk these up to the mechanical nature of the ringer and the age of the mic/speaker. After all, there’s a lot more energy involved in moving a hammer around than powering a little beeper.

Making calls

That night, I successfully ordered a pizza using an antique phone. Dialing was laborious, but novel for somebody my age, and honestly kind of fun.

Monthly costs are minimal, only $0.80 for the DID number and an additional $0.005 per minute. Calls are clear and sound great, and after nearly a month of use I can say that it’s reliable and solid as a ’landline’ replacement. Plus, it makes a great conversation piece!

There are certainly improvements I would could make, for example adding SRTP to add another layer of security for my calls. It would also be nice to add additional handsets to my house to build an ‘intercom’ - that is if I can find more old phones.